Den Text in englisch können Sie untenstehend lesen. Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Michael Durgin und Jürgen Schweitzer, Herausgeber “Graphische Kunst”, Edition Curt Visel.

Eldorado von Désirée Wickler | Michael Durgin | “Graphischen Kunst”, Heft 1/2020, Edition Curt Visel

Michael Durgin, Mitbegründer und langjähriger Herausgeber des Magazins “Hand Papermaking” (-> externer Link) schrieb über das Künstlerbuch ELDORADO für das Magazin “Graphische Kunst“, Heft 1/2020 der Edition Curt Visel (-> externer Link).

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Eldorado by Désirée Wickler

Michael Durgin

Artists have been depicting the Dance of Death since at least the early 15th century CE, when it was painted on a cemetery wall in Paris and on the wall of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Related to the older tradition of memento mori (“remember, you must die”), it represents the stark reality that death comes for us all, no matter our station in life. Hans Holbein the Younger’s woodblock series (carved in exquisite detail by Hans Lützelburger and first published in 1526), depicts death as a skeleton, paired with different figures, from Pope and Emperor to Ploughman and Beggar. Death is the great leveler and in Holbein he not only obliterates the power of the mighty – such as skewering the knight with his own lance – but also lifts up the lowly, if only a little bit – taking over the plough and telling the ploughman to rest after a long life of work. Of course, this “rest” is death itself.

Holbein made his woodblocks in Basel, at the height of the Swiss Reformation, and his depictions of church leaders is harsh religious and social critique. So too, many artists since have used the theme to comment on their own times. Hap Grieshaber’s Totentanz von Basel (VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1966), for example, updates the Baseler Totentanz that had been painted on the cemetery wall near the Predigerkirche in Basel c. 1440 (destroyed in 1805). In addition to the traditional pairings with death, Grieshaber depicts in his woodcuts more contemporary characters, such as a Jew suffering at the hands of Death as a Nazi. A more recent work, Tanz mit dem Totentanz (Hartmut Kraft, Salon Verlag, Köln, 2007) shows the work of twenty-five contemporary artists reflecting on Bernt Notke’s 15th century depiction at the Marienkirche in Lübeck, destroyed in March 1942, during World War II.

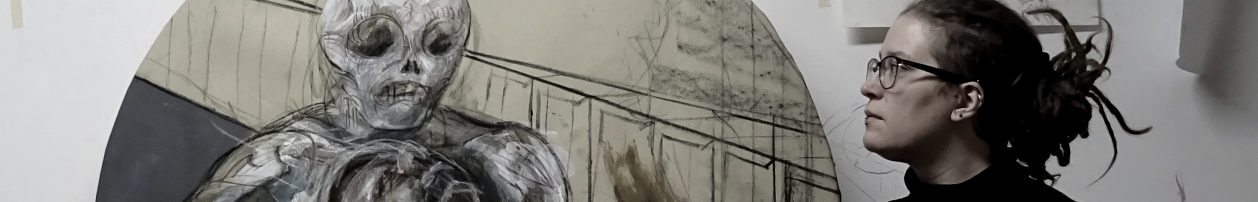

The Dance of Death remains relevant today. It was popular during the years of the Black Death in the 15th century and we now have our own plagues: SARS, Ebola, and COVID-19. While specific threats and terrors have changed, the inevitability of death remains and Désirée Wickler continues the tradition of giving the Dance of Death a contemporaneous perspective. Born in 1983 in Luxembourg, Wickler brings an acute awareness of her times to her art. She is keenly interested in the social dangers of overconsumption, environmental destruction, commercialization, corporate control, and recurrent nationalism. Her figures exhibit an intense, visceral vitality, evoking the violent and expressionistic mindset of street fights and mixed martial arts.

Wickler made a series of twenty-four large drawings on canvas for her multi-media project, Eldorado, installed in 2019 at Neimënster Cultural Center, a former Benedictine abbey in Luxembourg City. Over the years, the abbey had also been used as a military bastion, an orphanage, and a prison for Germany’s political prisoners during World War II: uses associated with suffering, oppression, and death. Within the square cloister, the drawings filled its twenty-four arched spaces in a continuous sequence. These could be seen from different perspectives through the openings between the columns that lined the walkway which, in turn, covered the bones of the dead. A continuous, low-volume sound installation played in the cloister, with recorded poems by the Austrian writer Sophie Reyer, composed in collaboration with sound artist Michael Fischer.

Each drawing depicts Death, appearing as a pale-fleshed skeleton, paired with a human figure. The humans are young and muscled, caught in positions of struggle. Sometimes Death even appears at a disadvantage. Wickler draws on opulent, patterned surfaces, with large sections of solid colors and gold foil, and incorporates many references to contemporary culture: corporate symbols and logos, slogans, and emojis.

All of this background material is stripped away in the artist’s book; only Death and his victims remain. The book, also called Eldorado, functions as a distillation of the paintings, preserving the essence of the twenty-four figures with their wrestling forms, but removing the context and rich backgrounds of the drawings.

Wickler designed the book in a Leporello (accordion) format, in the shape of a coffin, the angled folds creating a circular form when the book is opened. The paper’s color hints at the walls of the abbey and the pages have uncut deckle edges, which draw the viewer closer. Each paired image of Death and figure roughly fills one panel of the book, but some overlap onto adjacent panels, in a procession that links the images. Importantly, Wickler has depicted Death via watermarks made in the paper, while his dance partners are printed in transparent ink, which shows darker than the supporting paper. The figures from the large drawings are thus reproduced but in a way that defies immediate recognition. Because each page relies on both transmitted light (for the watermark) and reflected light (for the transparent-ink image), the combined, carefully registered figures can only be viewed together from certain angles and under specific conditions. This aesthetic choice alludes to the mystery of the phenomenon of death, as a shadow that surprises people when they least expect it.

The effect is striking, whether each panel is viewed alone, with its adjacent panel, or as the full series of 24 images. The tactility of the handmade paper, the format, and the necessary light for viewing the images force the reader to interact with the book, raising it in the air and looking at it from multiple angles.

The artist worked closely with master papermaker John Gerard to design the paper and its watermarks. The thickness and opacity of the paper, sized and made from hemp and cotton fiber, had to be rigorously controlled to support both the watermarks and the transparent ink printed on it. Wickler had to simplify and reduce her large, complex drawings, using lines no thicker than three millimeters, to provide the optimal stencils for the watermarks. The graphics were then transferred to self-adhesive foil using a plotter, then peeled off and placed directly on the papermaking mould. Gerard used a template to mask out parts of his mould for the coffin-shaped pages, so that paper pulp would not collect there during sheet formation. Gerard’s expertise in designing the equipment and producing the paper to these exacting specifications was crucial to the success of the book.

While the book itself is restrained and concentrated, the box that houses it reflects the opulence of the drawings. Bright yellow book cloth covers the custom-made enclosures and the book rests in a rich, brocade, coffin-shaped inset. The title is deeply printed in matching yellow hot foil type on the spine. Handmade paper is inset into the covers, in the shape of the installation drawings and reproducing one of the paired figures inside. The human is on the front, printed in transparent ink, and death is on the back, printed in white. The blind-stamped title is embossed on the front, and backward reading and debossed on the back, as though the impression of the letters had pressed down, straight through the box. Wickler worked closely with bookbinder Norbert Hoffman in designing the box and he then completed the edition.

The book functions well when accompanied by the handsome exhibition catalogue (itself a kind of artist’s book). Through full-color illustrations of the large drawings and other related elements of the exhibition, the catalog helps give full context to the refined elegance of the book.

Wickler’s work will certainly not be the last depiction by an artist of the Dance of Death; the guiding metaphor is both powerful and timeless. But as a milestone in the tradition of this theme, Eldorado is a significant work, masterfully designed and exquisitely made.

Courtesy of Michael Durgin and Jürgen Schweitzer, editor of Graphische Kunst, Editon Curt Visel.